Since my last brief discussion of herky-jerky rhythms and pondering

Michael Kaulkin's comment on it, I've been wondering more about the assumption that we need to count in a regular fashion, that is, where every counted beat is the same temporal distance from the last counted beat. There seems to be an emphasis in classical music on the square simplicity of the mathematics involved in the way that rhythms are approached, that a rhythm of (say) a quarter and a dotted quarter and an eighth is

really happening over a regular beat of 3 quarters, instead of just

being a rhythm of this followed by that followed by so-and-so. I'm sure, absolutely sure, that this is not the way of all music. It's not the way I played music in my misspent youth in r&r bands for sure. I remember trying to teach Henry Kaiser a 'lick' many years back, the rhythm of which was a standard rock something like 2+3+3 but I couldn't explain it in that way to him. The conversation went something like:

Erling: (playing the part as envisioned) Just like this.

Henry: (playing something so much more complicated, say 2.12 3.41 2.77) OK, got it.

Erling: (blinking, confused, playing it again) No, more like this, listen.

Henry: (now trying 2.21 3.03 3.44) Right, no problem.

Erling: (trying desperately to comprehend the higher mathematics involved, some continued fraction expansion or log base something or set of measure zero blah blah) Ha, well, that's close, but it's more like...

(process iterates for a bit)

Erling: (suddenly gaining insight) Um, Henry, the interval between the first two is just a little bit shorter and the interval between the next two is just a little longer.

Henry: (playing it, just a little better)

Erling: (emboldened) Right, now just a little longer between the second two and I think you cut in too much on the first...

Henry: (playing it even better)

Not wanting to press the point here, but just to be clear: the insight is that there was absolutely no underlying time base at all, simply intervals in succession. There was no abstraction of rhythm, this was it, events in time laid bare. I wondered at the time if this might have been one of those interesting neurological 'deficits' that Oliver Sacks is so fond of popularizing, but since then I've thought not. Henry once tried to teach us a Captain Beefheart tune, Alice in Blunderland, explaining it in the fashion above. We had a very difficult time of it until we realized it was just in 11 or 13 or some other easily approachable prime numerated time signature and then it fell into place, and we congratulated ourselves on one more case where the old fashioned model worked la di da. But Henry was proud of his model of the musical world and clearly believe it to be meet right and salutary, and his level of non-abstraction really went quite deep, I mean what do we mean when we say this is the same rhythm at a different tempo, I mean we know what this is, a simple affine transform applied to the time-interval-sequence, but why do we think that is the same? In another amazing display, I once realized during a concert that Henry was playing the tune quite correctly, in that it was internally consistent (re: the affine transform above), but just a little teeny bit faster than the rest of us and he continued doing that until he reached the end - quite a few seconds before us. Have you ever tried this, e.g., in the phase pieces of early minimalism? It's really quite difficult to do on purpose, but the performance matched his model. We simply weren't playing the events at the right time offsets relatively to the onset of the piece and he was.

Over the years I've realized that I am just a bit like Henry, a bit more comfortable thinking of music as a chain of intervals, not quite as irrationally related, but still, not regular at all. I've often approached the music I've written this way. When

Guy Garnett and I worked for Yamaha and bought the first copy of Finale hot off the presses - the one that came with the videotaped testimonial of the importance of

Jesus Christ in the development of

Computer Notation Systems - we were surprised by its measure-centricity, which still remains in the program to this day. We didn't get it. Weren't bar lines merely added after one wrote the music simply to aid the performer in her perceptual chunking? I don't pay much attention to my bar lines when I'm playing my own music and I really have to contort my perception of my own music when I'm playing them under the yoke of a conductor, doing what so many musicians do, breaking out the pencil and painstakingly marking the regular pulses above the irregular timeline of the score so I can map their notions onto mine. I was taught in

composing school to aid this process, to make sure that my (at that time highly) irregular and polyrhythms were broken up with gazillions of ties and whatnots to fit into groups based on the denominator of the time signature in order to make this mapping of the irregular to the regular as easy as possible for the poor performer, handcuffed to the regular beat, the incessant and regular beat, like the beating of the heart under the floorboards, the drip drip drip late at night of the leaky faucet, the tap tap tap of the tree against the window, like the invention of Hippolytus de Marsiliis, slowly but inexorably driving us insane.

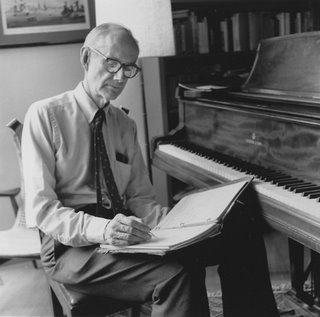

But why can't we 'count' in a natural way, an irregular beat that wafts and waves with the tune, with the rhythm? This is the way we are supposed to play the Dance of Fury for the Seven Trumpets, yes? And those added dots sprinkled here and there in the Concord Sonata? And the tempo changes cum polyrhythms of Klavierstücke I-IV? And Michael Gordon's Trance (pardon, stolen from Kyle Gann's blog):

And speaking of the aforementioned reverend Mr Gann, the Zuni

Buffalo Dance that seeded his totalist interest? Are we supposed to tap our toes in some regular fashion through this minefield of events in time? Right, I didn't think so.

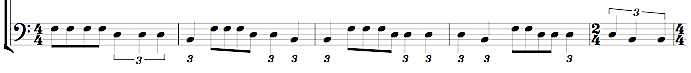

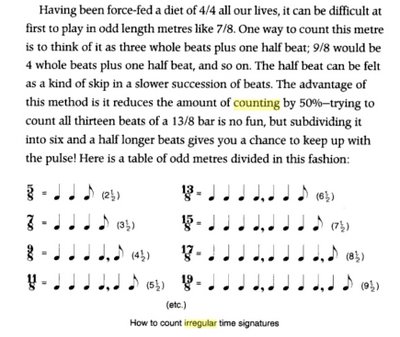

Finally, from Dave Stewart's book Inside the Music, a book written, I might point out, for the popular musician, to wit:

Labels: composition, music, rhythm