Composing music is a strange ephemeral artform, constructing something from the almost nothingness of sound, pressure-wave vibrations of the air. But this strange ephemera is somehow able to touch deep inside the listener, bringing up emotions and reactions pleasant and unpleasant but impossible to ignore. In the films of the Hollywood mainstream, the emotional power of music and its ability to pass by the viewer's defenses is often used to manipulate, to subliminally broadcast to the listener how they are supposed to feel. But music in Jon's films is different. Although it carries a large part of the emotional weight of his films, it is not a hidden wedge into the viewer's heart. In fact, it is usually banished from those scenes which are the most directly narrative and kept to those long minimal moments of repose that are so dear to Jon. It is given an equal billing, with narrative, with the landscape, with the characters, part of a set of parallel threads that each relate to the viewer a different aspect of the story.

I first met Jon at a screening of All the Vermeers in New York at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley California. The producer, Henry Rosenthal, whom I had known through the Just Intonation Network years before, called me and told me I had to come, that it had been a labor of love and that he was quite proud of it. When I saw it, I was enraptured. I loved the look of it, the pace of it, the feel of it, and especially the music by Jon English. It was such a musical film, both indirectly, with a feel for rhythms on the short and long and architectural scale and directly, leaving space for musical development that Jon English filled so beautifully, especially in the long tracking shot dancing among the columns of the lobby of some Wall Street location.

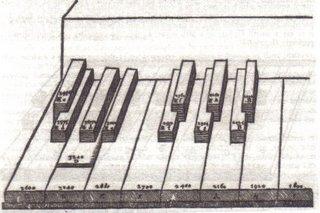

A few years later, as Jon Jost's Sure Fire needed to be finished for its debut at Sundance, Henry called me while I was staying in a room in a businessman's hotel in Japan that was the size of a smallish shoebox and told me that Jon English was too ill to finish the music, in fact that he had written only a short melody for pedal steel; that the music had to be done in a couple of weeks; that it needed to be in a country style and that it also had to be in just intonation. I jumped at the opportunity. When I returned from Japan, I got a videotape of the film in its almost-finished state and wrote the music very quickly, sketching out a primarily synthesized score, starting from the melody that Jon English had written, and bringing in his pedal steel player to improvise with me. There were some brief meetings with Henry and Jon Jost, where they pointed at large problematic sections and told me to fix them, but mainly I was left alone to do what I wanted inside the constraints of no budget and no time. Jon did tell me there were some important numerological features of the film centering around the number 13, which I worked into various rhythms and various pitch ratios.

As Sure Fire was completed and as Jon and I spent more time together, we had an opportunity to work in a more relaxed fashion. He started to tell me of his plans for the next film, The Bed You Sleep In. Jon had written bits of a script and said that he wanted some music done before production so that he could play it for the actors while they were working. He also told me one of his recurring ideas, that he had always wanted music that naturally came from the location sound, sometimes imperceptibly. But he also wanted real music, not just sound, and I suggested a mixture of classical and folk and electronic instruments, and a mix of classical and popular styles.

From the notes to the CD:

During the production of the film, John Murphy, who was doing the location recording, took me into the sawmill featured in the film. Walking through the mill was like listening to a great industrial/futurist composition, the sound wonderfully dense and richly spatialized. The sounds and smells of the local mills, especially the Georgia Pacific plant, were present throughout the town of Toledo. The sound of the GP plant was audible in all the location recordings, whether inside or out. The plant sat at the side of a tremendous chemical lake, a dirty brown pool with fountains spraying noxious liquid in large plumes up from the surface. Its presence so overwhelmed me that, at one point, I had decided to do all the music using the sounds of the mill and the GP plant. In the end, I used a variety of sound sources. Some of the music, notably that which frames the letter scene, is generated almost entirely from sampled and processed recordings of the mill made by John Murphy during the production. Some of these samples are used as instruments in other pieces and are mixed with the acoustic instrumental ensemble. [...]

After the production, Jon and Mark Redpath started editing and I began to see the film that didn't exist in the screenplay. There were many long, static shots where Jon wanted the music to firmly imprint the film's bleak emotional state. There was an extensive use of split screens. There were a number of musical dichotomies I intended to be analogues of this, but the most successful [were in two scenes]. The first was a spare statement, where a single tone split into two diverging tones. In the second, where the screen collapses in on itself, a similar divergence occurred in a rich instrumental texture, causing the harmonies to quaver and shift in a continuous manner.

I went with Jon and Henry to the premiere of The Bed You Sleep In at the Berlin film festival where, unfortunately, Jon and Henry had a falling out over disagreements about control and ownership of the films they had done together. By the time Frame Up was completed, for which Jon English wrote the music and I did some sound work, the two of them were completely separated. But, in late 1994, Jon asked me to come to Vienna to begin work on Albrechts Flügel, a film about a second violinist in the Wiener Symphoniker, a person who, like so many of us, comes close to greatness, almost achieving it, but who is painfully aware that they will never succeed. It is so sad to me that this movie never came to fruition. The music was to have been an integral part of the film, part of the narrative and a lens through which the characters saw the world. Jon and I talked many times about the music and the ideas in the film. I worked with one of the actors, an amateur violinist, and I started to work on some music, including what became the Albrechts Flügel suite of piano pieces. This, I thought, would be the next step in our artistic relationship, a close partnership from the beginning of the film, hinted at in Bed, but taken even further. But the film fell apart when Jon discovered some irregularities in the handling of the financing for the film. I was never clear exactly what happened, but he left Austria and settled in Rome, where he finished Uno a me, uno a te e uno a Raffaele.

Soon after, Jon turned away from narrative films, playing with the flexibility and affordability of cheap digital cinema, first with Nas Correntes de Luz da Ria Formosa, a beautiful meditation on a fishing village in Portugal, and later London Brief. I worked with Jon on the latter film, but only from a distance. I wrote a number of pieces, all electronic works, based on what I saw in his early drafts. I gave him a free hand in using those excerpts, placing them where he wanted, cutting and adjusting them. I know he liked the intimacy and control of the new medium, that he could sit and work and recut and change everything at his computer by himself without having to worry about cutting room rental costs, sound engineers, and so on. I think, in his heart, Jon wishes he could do it all himself. He wrote the music for some of his early films and has a strong musical sensibility and, finally, is a person with a strong overall vision.

Since that time, I have contributed music for a couple of his films after his return to narrative filmmaking: Homecoming and La Lunga Ombra. I'm sure that, sooner or later and his recent cancer scare notwithstanding, I'll do more. But because of our separation - Jon is in Korea these days - and the lack of money available for Jon's work and therefore for my time, there hasn't been quite the same level of connection as when we did Bed and Sure Fire, when we used to play table tennis together (Jon and I are both very competitive) and talk in detail about the films and how the music should act in them. Maybe it can happen again. I hope it does.

photo by mica scalin

My son said yesterday that it would be expedient for me career-wise to spend a bit of time in prison, especially for a political crime. Maybe that's more likely currently, here in the land of Mussolini and Berlusconi than back in the sun soaked bliss of whatever San Francisco. In Roma my thoughts have turned to the various Italians I have known and loved: Nono and Berio and Dallapiccola. The budding latter young Luigi did spend some career enhancing time with his family in a camp for subversives in Graz, the hometown of our own favorite California National Socialist and Führer, but the connection today is a mention of myself in a discussion here on whether Dallapiccola may have wanted to have his music played in JI or some other non-equal tuning system. I felt compelled to correct a small error. A statement on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: I often need to correct others' mistakes, answer yes. JI and tuning history in general is still so misunderstood, and the recentness of the God-given nature of 12 equal so little known, that I do feel I need to say something from time to time just to rail against the darkness etc. Once again I feel the need to retune my life and music a bit.

My son said yesterday that it would be expedient for me career-wise to spend a bit of time in prison, especially for a political crime. Maybe that's more likely currently, here in the land of Mussolini and Berlusconi than back in the sun soaked bliss of whatever San Francisco. In Roma my thoughts have turned to the various Italians I have known and loved: Nono and Berio and Dallapiccola. The budding latter young Luigi did spend some career enhancing time with his family in a camp for subversives in Graz, the hometown of our own favorite California National Socialist and Führer, but the connection today is a mention of myself in a discussion here on whether Dallapiccola may have wanted to have his music played in JI or some other non-equal tuning system. I felt compelled to correct a small error. A statement on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: I often need to correct others' mistakes, answer yes. JI and tuning history in general is still so misunderstood, and the recentness of the God-given nature of 12 equal so little known, that I do feel I need to say something from time to time just to rail against the darkness etc. Once again I feel the need to retune my life and music a bit.